The 2021 Federal Budget announced the Government’s intentions to launch a consultation with charities about “potentially increasing the disbursement quota…beginning in 2022.” Any increase of the disbursement quota (DQ) rate above the current 3.5% annual requirement will have significant implications for the charitable sector, foundations and donors. Below is a longer than usual analysis of what it means and what to expect.

Budget Announcement

The Budget announcement is curiously coy. Why didn’t the Government (and the Department of Finance) state a new DQ rate? Canada has a lower DQ rate than many of its peer countries. The U.S., for example, mandates 5% per annum. Getting foundations to grant (or spend on charitable purposes) at a higher rate is low cost and, seemingly, politically low risk.

According to the Budget, private and public foundations collectively held $85 billion at the end of 2019. In 2021, it’s likely $95 billion. These funds have already been donated, receipted and are tax exempt. Why not mandate that they be spent faster and at higher rate? The Budget suggests that a DQ boost could “increase support for the charitable sector and those who rely upon its services by between $1 billion to $2 billion annually.”

So why a consultation process? Why now, especially after the charitable sector has been having an active debate around the concept of raising the DQ? What more needs to be known?

Clarity of Direction

The coyness is particularly intriguing because the Budget outlines the Government’s intent and thinking. The Budget expects a $1 to $2 billion increase on a $85 billion base of assets. Do the math. A 1.5% increase to get to 5.0% would be $1.27 billion. On $95 billion it’s $1.4 billion.

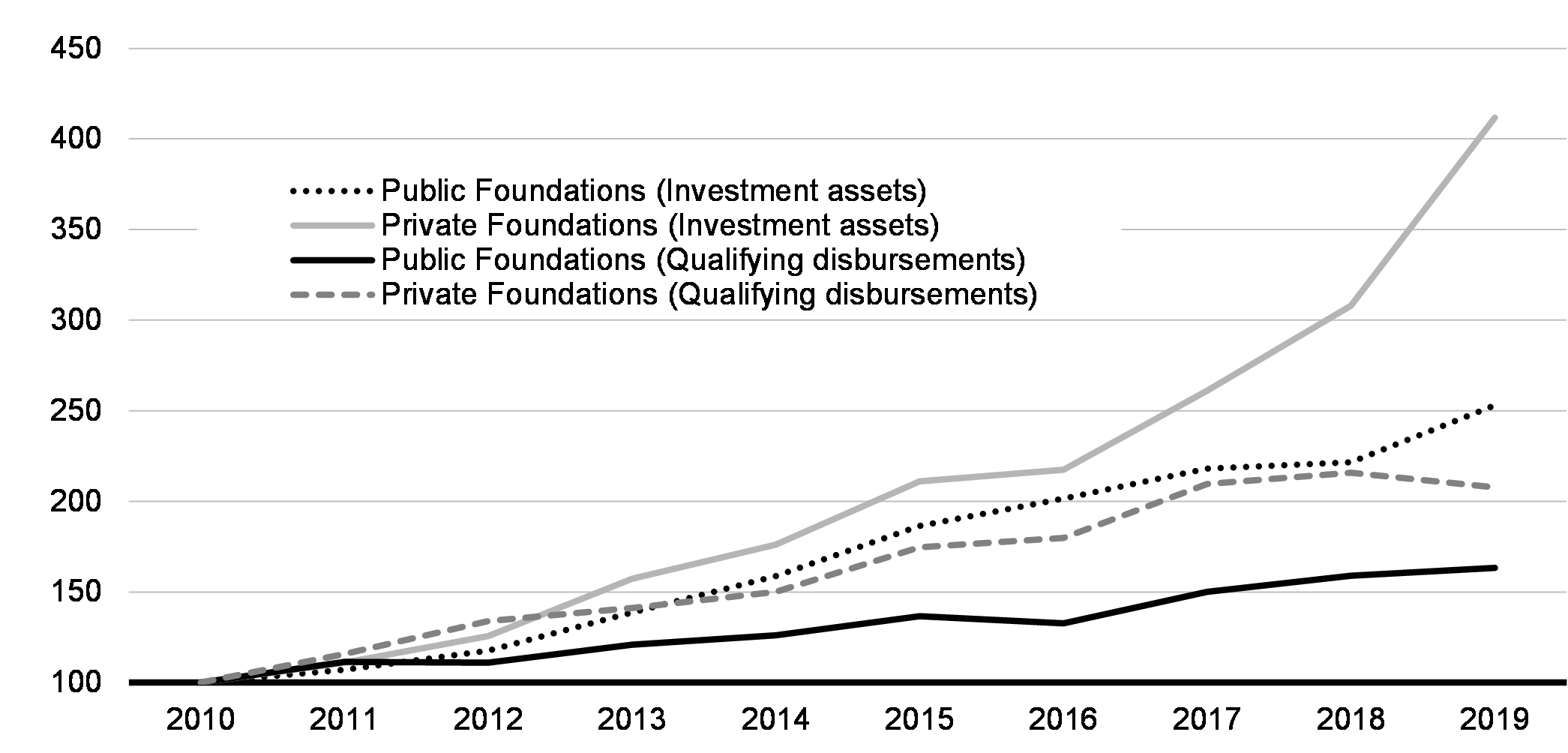

The Budget is also clear about the targeted charities. The 3.5% DQ rate applies to all types of registered charities: charitable organizations (operating charities), public foundations and private foundations. The Budget focuses attention on private and public foundations through an illustration showing investment assets and qualified disbursement of private and public foundations. Private foundations have a dramatically growing dramatic gap between investments and payout.

What the Budget doesn’t fully explain is the pace of asset growth. In 2006, private and public foundations held $23 billion in assets. In 14 years, foundation assets have increased by approximately 300%. One private foundation alone (established by a public corporation) has assets of $35+ billion and is not currently meeting the 3.5% minimum (which is, on the face of it, a CRA compliance issue).

Taken as a whole, this is huge build up of charitable capital. It is partly due to the generous donation tax benefits available to Canadian taxpayers. In other words, the value of endowments has increased dramatically, and Ottawa is, arguably, making a responsible policy response.

Endowment Thinking & DQ

The other factor in the background of the DQ announcement is the change in thinking about charitable endowments. Historically, endowments and DQ provisions of the Income Tax Act were based on trust principles. There was a separation of capital and income. Capital would be invested and only income would be distributed annually in the form of grants or other charitable activities.

Historically, this system enabled the concept of a perpetual or permanent endowment. Capital was sacrosanct. Only income could be used for annual funding needs. A trust-based rule in the old DQ regime was the “10-year” gift, which effectively stipulated that the capital of lifetime donations for endowment had to be held for ten years. This worked well in the era of high interest rates.

In 2010, post financial crisis, the DQ was updated. The DQ provisions based in trust law were abandoned, including the 10-year gift rule. Implicit in these changes was a move to away from trust law models towards total return investing and annual payouts from income, capital gains or even capital, if needed. This change to the underlying philosophy of the DQ system has not been fully understood by foundations or advisors. The 2010 changes, however, enable an increase in the DQ rate because the system is no longer dependent on annual income alone.

DQ Rate

The DQ rate has changed several times since the 1970s. Pre 2004, the DQ rate was 4.5%. Foundations advocated for a reduction to 3.5% due to the low investment yields at the time, which are even lower now. After years of high interest rates, foundations needed to shift to mixed portfolios of equities and bonds — and use capital gains – but that shift in thinking was slow. The 2004 Budget said the 3.5% figure was “more representative of historical long-term real rates of return earned on the typical investment portfolio held by a registered charity.” This statement acknowledged the shift to total return, but still gave priority to capital preservation over current spending on mission.

A 5.0% DQ rate may lead to some erosion in the original purchasing power of capital of a long-term charitable fund over time. Of course, the erosion rate will depend on the investment performance and the expense management of foundation over time. By setting the DQ rate at 5.0% the Federal Government would be saying it wants to see more current benefit to charities and the people/causes they serve. These are tax receipted and tax-exempt dollars. A 5% rate would also indicate that preserving capital and perpetuity is a secondary goal, at least from a public policy perspective.

As I have previously addressed, there are other factors that inform the DQ apart from a single number. The 3.5% rate is based on previous 24-month market average of property not used directly in charitable programs. Charities can build up a DQ surplus and carry them forward for five years. Trust restrictions on individual gifts and endowment funds can prevent higher payout rates, whatever the Income Tax Act says. It is a complex regime that has flexibility and can be complicated by underlying trust restrictions.

Concerns and Objections

Again, why didn’t Finance specify a number in the Budget? For starters, I think they are expecting push back from powerful players in the charitable sector, especially among private foundations. There is a wide-spread belief that DQ rates should be a minimum (3.5%) and discretion should sit with the Board of Directors, not with the Income Tax Act.

Moreover, there is a genuine belief in the importance of perpetual endowments and foundations, both among private and public foundations. I have heard foundation directors complain about increased expectations during a historically low period of investment yields. It’s easy to forget we’re also in an extended equity bull market.

This conservatism is also supported by several charitable sector umbrella organizations. I am not aware of any at this stage that are advocating for a DQ increase. Understandably perhaps, caution rules the day. Why piss off members and funders?

In the broader charitable community, there are a lot of advocates for higher granting rates, but few that are actively engaged with the issue. They are unlikely to show up to consultations or submit letters. So, it is up to the Department of Finance to negotiate this one with foundations and umbrella organizations. The public servants are praying that the Prime Ministers office will not receive too many calls from this constituency.

All in all, we’re in for an interesting time over the next few months. Stay tuned.

0 Comments